Mixed Messages

Cory Panshin on March 7, 2013This seems like a good time to pull the camera back and take in a broader field of view.

I’ve been speaking up to now as if the lives of our earliest ancestors were devoted entirely to constructing elaborate mind-maps of their experiences and then expanding them into visions of higher possibility. However, that isn’t how people live today, and it certainly wasn’t the case then.

For one thing, not all humans are equally imaginative. Some participate enthusiastically in bringing the latest visions into being, but a larger number couldn’t care less. And even the most creative among us spend much of their time caught up in the petty round of everyday routine.

So sharp is the division that we might be said to inhabit two different realities at once — call them the realm of understanding and the realm of instinct. And this split would have been even more profound at the start, when the life of the mind was still something new and limited and the greatest part of our existence was governed by deep, ancestral rhythms of sex and dominance.

Those rhythms apparently go back to the emergence of Homo erectus, some 1.8 million years ago. That was when we committed ourselves to a ground-dwelling way of live, lost our body hair and acquired our present set of secondary sexual characteristics, and gave up chimp-like mating patterns in favor of a system of permanent pair-bonding that enabled us to nurture our big-brained offspring through an extended period of infancy and childhood.

These same instincts are still hard-wired into us, but their expression has been greatly moderated by the moral teachings of a long succession of visions, each of which has done its part to make us a little less animal and a little more human.

When the first three visions were going through their initial development, however, this moderating influence could not yet have taken hold. Even today, the newest visions exist on the margins of the culture, inspiring artists and philosophers but having little worldly impact. It is not until they give up their initial focus on transcendence and turn to more practical matters that the moral aspect becomes predominant.

As I suggested in the previous entry, the oldest of the visions is likely to have entered upon that transition soon after the onset of a major ice age about 200,000 years ago. In the process, it began to assume intellectual authority over the ancient instinctual processes of birth and death, growth and decay — and as a result, the two formerly separate spheres of human existence started to become entangled.

This state of entanglement may initially have been most apparent in the wearing of clothing, which according to recent studies of the DNA of human body lice commenced on a regular basis roughly 170,000 years ago.

As long as our ancestors habitually went unclothed, their naked bodies would have continued to send out the same simple messages that went back to the time of Homo erectus: I am fertile. I am powerful. I am young and need protection. I am old and deserve respect. But clothing inevitably modifies those messages — sometimes concealing, sometimes exaggerating, and sometimes simply redefining the raw facts of the human form.

And clothes do something else. They also serve as a canvas for the wearer to display statements about their own personality, their social status, and their beliefs about the nature of the universe.

Clothing is one of the most ancient human inventions for conveying symbolic meaning, second only to language and story. It is likely that even before the wearing of clothing became a universal custom, hunters and shamans and tribal elders had adopted distinctive garments and ornaments that expressed aspects of the earliest visions. And that symbolic function would not have vanished as clothing became a part of everyday life but would only have intensified.

Both functions, the instinctual and the symbolic, are still very much in evidence today. Our clothes shape our appearance in ways that speak to our most primal instincts, but we also use them to signify our allegiance to one or another of the current visions and to indicate those visions’ basic principles and moral standards.

For that reason, it is worth examining the relationship between fashion and the visions for any clues it can offer about the crucial changes that began some 200,000 years ago.

Every vision gives rise to a characteristic style which starts off vague and ineffable but takes on definition and specificity as the vision passes through the outsider stage. During that stage, the primary role of the vision is to challenge the assumptions of the dominant partnership, and its typical style is correspondingly radical and provocative. Once the vision gains consensus status, however, its style is widely adopted and loses its insurgent edge. And by the time the vision is nearing the end of its lifespan, its style degenerates into nothing more than a marker of elite authority.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, for example, the top hat and tails that had been everyday attire in the late 19th century were retained only for presidential inaugurations or to affirm the status of England’s Prince Philip at an official function. At the same time, the unpretentious male business suit served to proclaim the egalitarianism of the democracy vision. And the outsider chaos vision was finding its classic bad-boy expression in the t-shirt and blue jeans worn with a swagger by James Dean.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, for example, the top hat and tails that had been everyday attire in the late 19th century were retained only for presidential inaugurations or to affirm the status of England’s Prince Philip at an official function. At the same time, the unpretentious male business suit served to proclaim the egalitarianism of the democracy vision. And the outsider chaos vision was finding its classic bad-boy expression in the t-shirt and blue jeans worn with a swagger by James Dean.

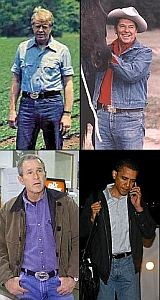

But when a dominant partnership fails, everything moves along a step. Between 1960 and 1980, top hats and tails vanished, business suits — now more sharply tailored — became the high-status garb of lawyers and government officials, and blue jeans were embraced as something that even presidents might wear in their off hours. At the same time, rebellious new styles like punk and goth began to express the themes of complexity, diversity, and bottom-up creativity that were central to the outsider holism vision.

But when a dominant partnership fails, everything moves along a step. Between 1960 and 1980, top hats and tails vanished, business suits — now more sharply tailored — became the high-status garb of lawyers and government officials, and blue jeans were embraced as something that even presidents might wear in their off hours. At the same time, rebellious new styles like punk and goth began to express the themes of complexity, diversity, and bottom-up creativity that were central to the outsider holism vision.

There is, however, something strangely subtle and metaphorical about the way fashions represent the visions. The messages are rarely obvious and may depend on our ability to decipher complex cultural references. Older generations are notoriously unable to “get” the significance of young people’s attire.

This is in contrast with the other type of messages that we send with our clothing — those that involve straightforward assertions of sex and dominance. These are universally accessible within a culture and to a great extent also translate across cultures.

And yet even these instinctual messages have the peculiar quality of varying in a regular manner that closely tracks the rise and fall of dominant partnerships.

That regular variation was the first clue I had of the existence of the cycle of visions. In the fall of 1972, I was reading books on the history of fashion and looking for meaningful patterns, and it suddenly struck me that over the past several centuries there had been an alternation every few decades between styles that emphasized gender-based characteristics and those that downplayed them.

During a period of what I came to label “organic” fashion, clothing is designed to draw attention to female sexuality and male dominance. Women’s clothes outline or amplify the curves of bust, waist, and hips, while the ideal male form is broad-shouldered and muscular.

During a period of what I came to label “organic” fashion, clothing is designed to draw attention to female sexuality and male dominance. Women’s clothes outline or amplify the curves of bust, waist, and hips, while the ideal male form is broad-shouldered and muscular.

During periods of “geometrical” fashion, on the other hand, the preferred body type for both sexes is willowy and adolescent. Women’s clothes often fall straight from the shoulders or bust to the hips, eliminating the natural waistline and creating a rectangular silhouette. Or else the skirt becomes so widely flared as to substitute a sharply pyramidal outline for the normal rounding of belly, hips, and buttocks.

There are a number of striking points about this alternation. One is its extreme regularity. During one extended period, all styles will be organic, and during the next they will all be geometrical, without any mixing or minor oscillations. Another is that this same pattern can be traced all the way back through history, though with the phases stretching out from decades to centuries and then millennia.

There are a number of striking points about this alternation. One is its extreme regularity. During one extended period, all styles will be organic, and during the next they will all be geometrical, without any mixing or minor oscillations. Another is that this same pattern can be traced all the way back through history, though with the phases stretching out from decades to centuries and then millennia.

And the third, and most surprising, is the intimate linkage between these alternations and the succession of visions. Every organic period without exception coincides with the era of a dominant partnership and gradually comes to an end as the partnership crumbles. And every geometrical period spans the time between partnerships — when the visions are undergoing rapid reorientation — and comes to its own end with extraordinary abruptness as a new partnership falls into place.

In the late 1960s for example, jeans for both sexes were hip-hugging and tight-legged. In the early 70s, they developed huge bell bottoms. But in 1978-79, bell-bottoms suddenly went out of fashion and were succeeded by women’s “designer jeans” that were closely molded to the female rear end.

As explained by Entertainment Weekly, “Retooling the boxy Levi’s look into formfitting pants with fancy stitching and big labels, designer-jeans makers pocketed nearly half a billion dollars in 1979. … Promising to make their wearers chic and sexy, designer jeans cost about $35, roughly twice the price of down-to-earth Levi’s. Racy TV commercials featuring flirting preteens and topless women helped them make headlines and profits.”

The extreme regularity of these alternations presents a number of puzzles, but my best guess is that they are rooted in our prolonged childhood and adolescence — a stage of life marked by an unusual flexibility of mind and willingness to learn new things.

During organic periods, we like to play at being grown up, and our highest goal is maintaining social stability. But during geometrical periods, when society is breaking down, we all become teenagers for a time, and even our clothing proclaims our receptivity to alternative possibilities and novel solutions.

Read the Previous Entry: The World Turns ColdRead the Next Entry: Forever Young